When the issue is violence in Brazil, each of us has already seen, heard or confronted some type of situation capable of causing fear, concern or even having physical or emotional consequences.

Crimes reported daily in the newspapers bring home the apprehension that exists in relation to insecurity in the country.

But there is another type of violence that may be very close and occur in a hidden and silent manner, which is often neglected: Sexual violence.

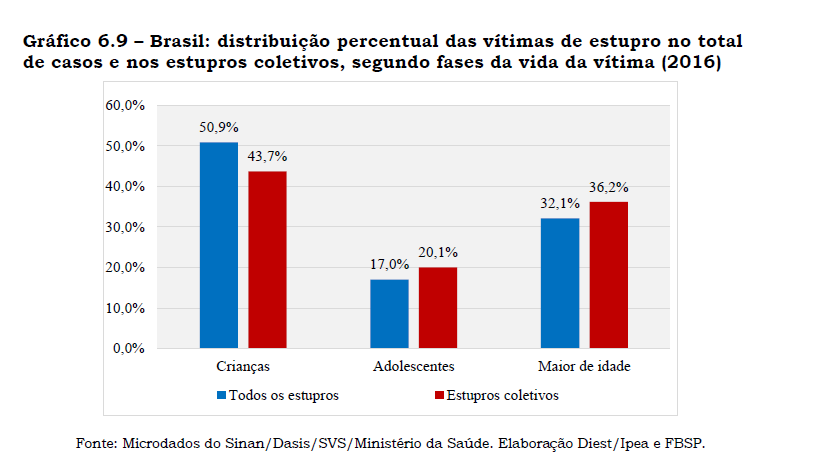

This is what is shown in the 2018 Violence Atlas. Produced by the Institute for Applied Research (IPEA) and the Brazilian Forum on Public Safety, the document was launched in June and shows an extremely alarming reality in relation to sexual violence against children and adolescents.The study indicates that “68% of reported rape cases in the health system relate to minors”.

Crianças – Children

Adolescentes – Adolescents

Maior de idade – Adults

Todos os estupros – All rapes

Estupros coletivos – Gang rapes

Source: Sinan/Dasis/SVS/Ministry of Health microdata. Prepared by Diest/IPEA and FBSP.

Living with the enemy

The study also indicated that “a third of the aggressors of children (up to 13 years of age) are friends and people known to the victim and another 30% are close family members, such as fathers, mothers, stepfathers and brothers.”

The negligence is evident when the numbers show that 54.9% of the cases refer to actions that had been occurring previously and 78.5% of the cases took place in the home itself.

The proximity of the aggressor and family negligence may explain another worrying finding: it is estimated that only 10% of cases of sexual violence against children and adolescents are reported.

The numbers show that, behind the crime, is a dangerous and harmful pact of silence involving victims, aggressors and family members. How then do we overcome this barrier, prevent the abuse or denounce it? The first step is education.

According to Luiza Eluf, a lawyer, prosecutor and Attorney General of the São Paulo Public Prosecutor’s Office from May 1983 to October 2012, sex education starting at six or seven years of age is very important. “Information and education are necessary for a healthy life. Above all, it is important to create an environment in which sexuality is natural, necessary and pleasurable, without taboos or prejudices,” she says.

Since 2007, sex education has been a focus of projects developed by the Instituto Criança é Vida (Child is Life Institute), based on very clear objectives:

- Help children and adolescents learn about their bodies, appreciate them and take care of their health.

- Avoid unplanned pregnancies, showing ways for adolescents to find guidance and use contraceptive methods.

- Share knowledge with institutions, families and children.

- Teach children and adolescents to protect themselves from coercive and exploitative sexual relationships.

- Help children and adolescents acquire knowledge that allows them to exercise their sexuality with pleasure and responsibility in the future.

In the “Time of discovery” cycle, educators become certified instructors to help children from 7 to 9 years of age understand, appreciate and take care of their bodies, and, importantly, to identify when the behavior of another person bothers them so that they are able to defend themselves.

In the “Yes, I can ask for help” instructional unit, educators are also taught to identify signs of sexual abuse in children, which can be physical, behavioral or appear in their relationships with their families, friends and at school.

Some of these signs include having an aggressive attitude, poor academic performance, anger, skipping classes, excessive embarrassment, sleep disturbances, fear of the dark, few relationships with classmates or friends, and changes in appetite. The handbook makes the important point that no isolated sign is specific to sexual violence and that an even larger set of indicative signs should be observed.

In the other two cycles of the sex education project, “Sex, love and responsibility” and “Issues of adolescence”, educators are provided certification courses to work with children from 10 to 12 years of age and adolescents from 13 to 15 years of age, respectively.

As important as preparing educators and children to identify abuses and ask for help, is ensuring adequate care and protection of victims. Otherwise, the pact of silence and fear that involves families facing this violence will not end.

Attorney Luiza Eluf, whose career has been marked by the fight for women’s rights, points out that, in most cases, the person who cares for and protects children is the mother. “Women are often afraid to denounce aggressors, because, in general, they have been taught to fear men and society. Women feel weak, without support to face a very delicate situation,” she says.

For Dr. Eluf, the way to break the pact of silence involves adequate actions by several spheres of government. “Governments, teachers and educators in general and school directors, as well as police and health secretariats are responsible for providing adequate support so that denunciations can be made and aggressors kept away from real or potential victims,” she says.

If educating is the first step in trying to prevent the sexual abuse of children and adolescents, the second step to interrupt this type of practice is denunciation. But hearing a child’s report of abuse suffered, especially when the abuser is a family member, is a quite difficult situation for the child, the other members of the family and those listening.

That is why Dial 100 was created. The National Denunciation of Sexual Abuse and Exploitation of Children and Adolescents Call Line is a service that allows the authorities to be informed of any serious suspicion of sexual abuse. The denunciation can be anonymous.

If the occurrence of sexual abuse by parents or guardians and, consequently, the violation of the Child and Adolescent Statute is verified, the legal authorities may decide to remove the aggressor or the child from the home environment as a cautionary measure.

From paper to practice

Although there is no shortage of laws in Brazil to deal with sexual violence, in practice, there is still a need to expand and provide instruction to the government services that care for victims.

A lack of personnel, delays in assistance, and limited operating hours in the Special Police Stations for Women, the bodies in charge of dealing with occurrences, are some of the problems Dr. Luiza Eluf points to.

In addition, “the legal authorities rely on a staff of medical experts and psychologists that are often not sufficiently qualified to assist victims of sexual violence, especially children,” says Dr. Eluf.

Moreover, the system is unfortunately not efficient in all regions of the country, nor do the responsible authorities give the matter its due importance.

For the attorney, the solution to ensuring that these types of crimes do not go unpunished is to apply existing laws, confront the machismo “of those authorities who often disparage and ridicule the version of the victim’s mother,” and ensure that there is technical staff qualified to objectively assist in cases where children have been sexually abused. “Only then will we be able to say that we have justice in Brazil!,” she concludes.